NOTE: The following op-ed article by the UNFPA Representative to Bangladesh was published on 20 June in two Dhaka newspapers, the Daily Sun and New Age. It coincided with the global launch of UNFPA's report on The State of the World's Midwifery.

When Shanu, 25, gave birth to a healthy child on May 4 in a local community clinic, she was crying with joy. She never thought she would have a child after what happened six years earlier… Shanu got married at the age of 17 and became pregnant after a couple of months. Living in a remote village of Thakurgaon district, where road conditions are poor and no health facility nearby, Shanu’s family members decided that her baby be delivered at home with the help of a local traditional birth attendant (dai). After more than 16 hours’ struggle, Shanu gave birth to her first child, but the baby had respiratory complications. A local village doctor was called in to try to manage the situation at home, but the newborn died later that night.

Shanu was unable to conceive for the next six years, but became pregnant again in mid-2010. This time, Shanu was registered as a pregnant mother, and she attended several mothers’ group meetings, where she received information about the danger signs of pregnancy, the importance of antenatal and postnatal checkups, birth planning practices, exclusive breastfeeding, and postpartum family planning. This was made possible with the support of the Maternal and Newborn Health Initiative, a joint initiative of the government of Bangladesh and three UN agencies (UNFPA, UNICEF ad WHO) to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in Bangladesh, funded by the European Union, UKAid and CIDA.

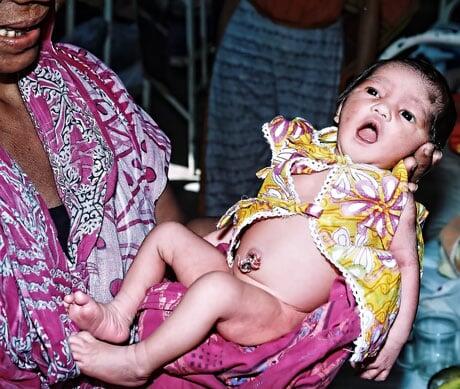

When labour started, Shanu’s husband contacted Merina, a community-based skilled birth attendant, trained by Kumudini Hospital, with the support of the initiative under the ‘Private CSBA Initiative’. She advised him to bring Shanu to the community clinic. Shanu was brought to the clinic at 5:00pm on May 4. She delivered a healthy baby at 10:00pm. Both Shanu and her husband were overjoyed to have this baby, delivered safely and at no cost.

Today, the first-ever ‘State of the World’s Midwifery 2011: Delivering Health, Saving Lives’ will be launched in Durban, South Africa, during the 29th Triennial Congress of the International Confederation of Midwives. The report, whose publication was coordinated by the United Nations Population Fund, reveals that unless an additional 112,000 midwives are trained, deployed and retained, 38 of the 58 countries surveyed might not meet their target to achieve 95 per cent coverage of births by skilled attendants by 2015, as required by Millennium Development Goal 5 on maternal health. Globally, 350,000 midwives are still lacking.

Despite significant progress in improving maternal mortality and reproductive health services in Bangladesh, there remain serious shortfalls in maternal health outcomes and access to services, particularly for poor women and for people in hard- to-reach and remote areas. The good news is that the maternal mortality ratio has significantly declined in the last nine years, from 320 per 100,000 live births in 2001 to 194 in 2010, according to the recent Bangladesh Maternal Mortality Survey 2010. But still, more than 7,000 women are dying every year while giving birth. More than 75 per cent of all deliveries take place at home and skilled health personnel attend only 26.5 per cent of all deliveries, with vast inequalities between the rich (53 per cent of whom have been attended by a skilled provider) and the poor (only 7.5 per cent had access to skilled care).

There is a growing international consensus on the critical role that midwives play in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity and sustaining the same. Investing in midwives is one of the soundest investments Bangladesh can make. Fully certified midwives, trained in accordance with international standards, are an essential workforce in an effective healthcare system and the best way forward to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality, as well as morbidity. A health system that can deliver for women and newborns is a health system that can deliver for all.

The Bangladesh prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, committed during the MDG Summit in September 2010 in New York to ‘doubling the percentage of births attended by a skilled health worker by 2015 through training an additional 3,000 midwives, staffing all 427 sub-district health centres to provide round-the-clock midwifery services, and upgrading all 59 district hospitals and 70 Mother and Child Welfare Centres as centres of excellence for emergency obstetric care services.’ This commitment is highly laudable and will tremendously help in achieving further reductions in maternal mortality and morbidity to achieve the Millennium Development Goal 5 by 2015. To operationalise this strategic direction of the prime minister, the government of Bangladesh, with the support from the United Nations Population Fund and the World Health Organisation, initiated a midwifery education programme in alignment with international and national standards to produce midwives with the required competencies.

To date, a six-month post-basic advance training curriculum has been developed, six training institutes have been strengthened with training aids, 20 faculties/teachers have been trained and 60 midwives have already been certified on May 5. These sixty midwives are under process of deployment in 15 upazila health complexes. The six-month post basic midwifery training is been scaled up to train another 50 faculties and 140 midwives by 2011. Simultaneously, the development of a three-year diploma direct entry midwifery programme curricula is under finalisation and the course is planned to start in 2012. This programme will slowly replace the 6-months training for a more sustainable and long-term solution for the country.

In the Mujabonni Community Clinic in Thakurgaon, Merina provides essential midwifery services to the women, children and families in her community. We need more community-based skilled birth attendants, like Merina, and midwives in Bangladesh, so that in the near future no woman dies when giving birth and no child starts her/his life without skilled care. The good news is Bangladesh is on the right track.

– Arthur Erken